In 2001, eight cocoa and chocolate companies came together to sign the Harkin-Engel Protocol, a voluntary agreement in which companies promised to eradicate child labor in the West African cocoa industry by 2005. Twenty years after the agreement went into effect, an estimated 1.56 million children work in the cocoa industry in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, which produce about two-thirds of the world’s cocoa. About 1.48 million of these children are engaged in hazardous child labor, which includes using a machete, carrying heavy loads -- often of cocoa beans -- and spraying pesticides.

Over the past decade, certification schemes like Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade International, and Fair Trade USA have become more prevalent. These schemes supposedly provide farmers with increased income, improved training, and increased access to the market. They “require” farmers to uphold certain human rights and environmental standards and then put their labels on cocoa products to mark them as allegedly free of labor and environmental abuses. Yet time and time again certification schemes have been shown to fail those who need them most -- cocoa farmers, their children, and their communities.

During recent investigations into labor practices on Ivorian cocoa farms, CAL found incidences of child labor on farms that sell to Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International certified cooperatives. Some parents explained that their children worked on the farms because the family couldn’t afford for them not to -- it was the only way for the family to eat. While this information is not surprising, it demonstrates that certification schemes have done little to improve conditions for cocoa farmers and their families.

This blog post first discusses evidence of child labor CAL found on Rainforest Alliance certified cocoa farms in Cote d’Ivoire. It then explains why certification as a system is failing cocoa farmers, their children, and their communities. It ends by explaining that the premiums Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International pay are not nearly enough for farmers to earn a living wage. Until farmers earn a Living Income, it will be all but impossible to end child labor in the West African cocoa industry.

Child Labor on Rainforest Alliance Certified Farms

With 1.56 million children working on cocoa farms in Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana, it is unsurprising that children also work on certified farms. In many cases, child labor, including hazardous child labor, is a result of the very low price companies pay cocoa farmers for their cocoa. While certification can increase farmers’ earnings marginally, the price companies pay for certified cocoa is still much too low. Unable to support their families, farmers often need their children to work on the farm simply to make ends meet. As one cocoa farmer who sells to the NECAAYO cooperative explained in August 2021, “They tell us that children are not supposed to work but they are the ones who help me feed the family. Children work in the plantations because the cooperatives and companies treat us so badly that we need to make children work on the plantations.” The NECAAYO cooperative was certified by UTZ through September 2021 (UTZ merged with Rainforest Alliance in 2018) and is certified by Fairtrade.

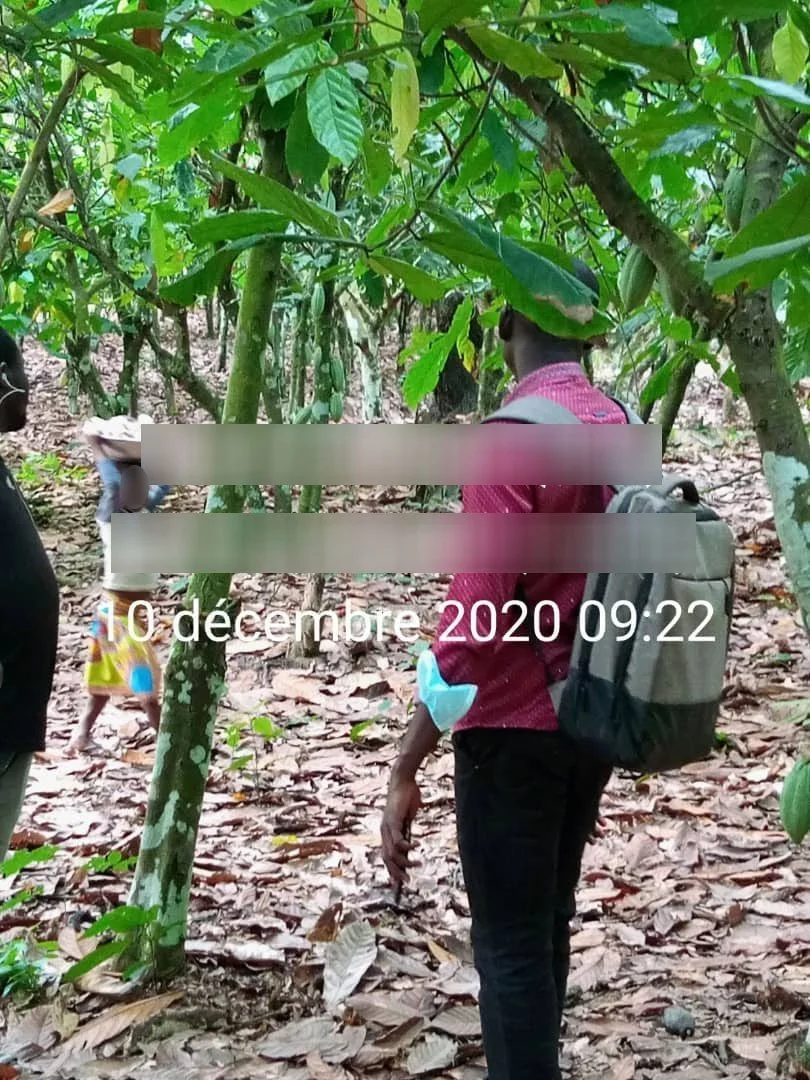

Investigators witnessed other instances of child labor on certified farms. For instance, in December 2020, investigators saw a little girl working on a certified farm near Aboisso, carrying cocoa pods on her head. The investigators learned that this farm sold their cocoa beans to the CNEK cooperative, which is certified by both Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International.

That same December, the investigators spoke with a small boy who was carrying a large bag of cocoa pods to an assembly point on a farm near Abengourou. This farm, they learned, sold its cocoa to the FAHO cooperative that was certified by UTZ through August 2021 and is certified by Fairtrade International.

The certification system is inherently broken. Given the failure to increase incomes, improve working conditions, and decrease the incidence of child labor on certified farms, one of the few remaining tangible benefits of certification is traceability. Certified and non-certified bags of cocoa beans are supposed to remain separate, allowing each bag of beans to be traced to a particular farm. Yet when the bags are loaded into trucks to transfer them for export, a bag of non-certified cocoa is often mixed with bags of certified cocoa, to increase the overall amount of cocoa. According to a truck driver picking up cocoa near Ketesso, drivers often add one bag of non-certified cocoa for every ten bags of certified cocoa beans, bulking up the overall amount of “certified” cocoa beans with cheaper beans. In doing so, the main benefit of certification -- traceability -- is also weakened.

Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International are Failing Cocoa Farmers

For years, there has been evidence that certification schemes have failed to help farmers and the environment -- their purported purpose. Certification standards certify cocoa farms, meaning they provide standards for labor practices and environmental protections that farmers are supposed to follow. In return for following these labor practices, cooperatives earn a slightly higher price or a premium on their beans, although the price depends on the certification program. (Rainforest Alliance pays much less than Fairtrade International.) Whether any of this premium makes it into the farmers’ hands depends on factors beyond the farmers’ control, including the size of the premium, how much of the crop was sold as certified, and how the cooperative manages the premium (which can be spent on educational programs and expenses of the cooperative).

Certification as a system is failing. Certification schemes have certain standards, yet in the case of Rainforest Alliance they are remarkably weak, especially for labor practices. The most glaring issue in the new 2020 standards is that they use an “assess and address” framework, meaning that farms with child labor, forced labor, and workplace violence and harassment can remain certified. (The farm must take steps after-the-fact to remediate the harm.) Rainforest Alliance further states that “Sustainability is a journey, not an end in itself,” an absurd statement when discussing basic standards for labor and environmental protections for the people and communities producing a luxury good.

Monitoring is also a major challenge in certification schemes. While auditing farms is supposedly a key tenet of both Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International, it appears that there is little actual auditing. A 2018 study found that, “self-verification” is the norm, meaning that farmers “self-report” to cooperatives whether they are abiding by certain standards. This presents a clear conflict of interest, since the farmers and cooperatives earn more when the cooperative is certified. When outside inspections do occur, farmers are often given advance notice -- making it unlikely that these inspectors would find blatant violations, such as children doing dangerous activities on the farm. As Nick Weatherill, head of the International Cocoa Initiative explained, “If you’re trying to use that light and occasional coverage to check for the occurrence of something that happens from one day to the next . . . you’re not really going to be picking up on the issue.”

Studies have shown that certification is failing in the most basic ways. Farmers often don’t know whether their farms are certified or not. The same 2018 study found that 95% of cocoa workers don’t know whether their farms or the farms where they are employed were certified or not. Even when farms are certified, farmers often don’t know what they are required to do to be certified. Farmers have reported selling both certified and uncertified beans and that the “labour standards for all beans were the same,” demonstrating that for cocoa farmers certification has little positive impact. One cooperative representative also explained that “they were unsure which farms were covered [by certification] since this changed year to year, and it is up to farmers to decide if they want to sell their beans as certified or not.” This mirrors what CAL saw on cocoa farms; the labor conditions were almost identical on certified and uncertified farms.

Rainforest Alliance And Fairtrade International Should Require Companies to Pay a Living Income for Cocoa

One main reason that Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International are failing farmers and their communities is that the price of cocoa remains far too low. The Voice Network has estimated the True Living Income for cocoa farmers in Cote d’Ivoire at $3,166 per metric ton. Yet the current farm gate price of cocoa is 825 CFA francs per kilogram, or $1,450 per metric ton -- less than half of the True Living Income. At this price, farmers are often unable to earn a living and don’t have a choice but to have their children work on the farm -- sometimes instead of attending school -- with the hope of increasing production.

Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International do differ in the price that they require companies to pay for cocoa. Rainforest Alliance requires only that farmers receive a $70 per metric ton premium for cocoa -- starting in July 2022. In contrast, Fairtrade International has a minimum price for cocoa, which it raised to $2,400 in 2019, when it also increased its premiums from $200 to $240. While this is a good first step, it is not enough. In fact, the Fairtrade International price remains more than $700 per metric ton below the Living Income. Additionally, cocoa farmers often are unable to sell all of their cocoa as Fairtrade International, meaning they do not receive the premium on all of their cocoa. This disincentivizes farmers to follow standards (when they know about them), since the costs associated with complying with the standards may be more than the increased income they earn.

The fact that children are regularly found working on certified farms is a clear sign that the current system isn’t working. Instead of slapping cute labels on products sold in the United States and Europe, cocoa and chocolate companies need to pay a fair amount for cocoa. It is up to Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade International to avoid complicity in such greenwashing and false advertising.

Allie Brudney is a Staff Attorney at Corporate Accountability Lab.